Metacognitive asymmetries in visual perception

Abstract

People have better metacognitive sensitivity for decisions about the presence compared to the absence of objects. However, it is not only objects themselves that can be present or absent, but also parts of objects and other visual features. Asymmetries in visual search indicate that a disadvantage for representing absence may operate at these levels as well. Furthermore, a processing advantage for surprising signals suggests that a presence/absence asymmetry may be explained by absence being passively represented as a default state, and presence as a default-violating surprise. It is unknown whether metacognitive asymmetry for judgements about presence and absence extend to these different levels of representation (object, feature, and default-violation). To address this question and test for a link between the representation of absence and default reasoning more generally, here we measured metacognitive sensitivity for discrimination judgments between stimuli that are identical except for the presence or absence of a distinguishing feature, and for stimuli that differ in their compliance with an expected default state. We find that the presence of local and global stimulus features gives rise to faster, more confident responses, but contrary to our hypothesis, has no effect on metacognitive sensitivity. In contrast, an additional post-hoc experiment confirmed robust asymmetries in metacognitive sensitivity for a classical visual detection task (detecting a grating in noise). Our results weigh against our proposal of a link between the detection metacognitive asymmetry and default reasoning, and are instead consistent with a low-level visual origin of this phenomenon.

1 Introduction

At any given moment, there are many more things that are not there than things that are there. As a result, and in order to efficiently represent the environment, perceptual and cognitive systems have evolved to represent presences, and absence is implicitly represented as a default state (Oaksford 2002; Oaksford and Chater 2001). One corollary of this is that presence can be inferred from bottom-up sensory signals, but absence is never explicitly represented in sensory channels and must instead by inferred based on top-down expectations about the likelihood of detecting a hypothetical signal, had it been present. Experiments on human subjects accordingly suggest that representing absence is more cognitively demanding than representing presence, even in simple perceptual tasks, as is evident in slower reactions to stimulus absence than stimulus presence in near-threshold visual detection (Mazor, Friston, and Fleming 2020), in a general difficulty to form associations with absence (Newman, Wolff, and Hearst 1980), and in the late acquisition of explicit representations of absence in development (e.g., Sainsbury 1971; Coldren and Haaf 2000; for a review on the representation of nothing see Hearst 1991).

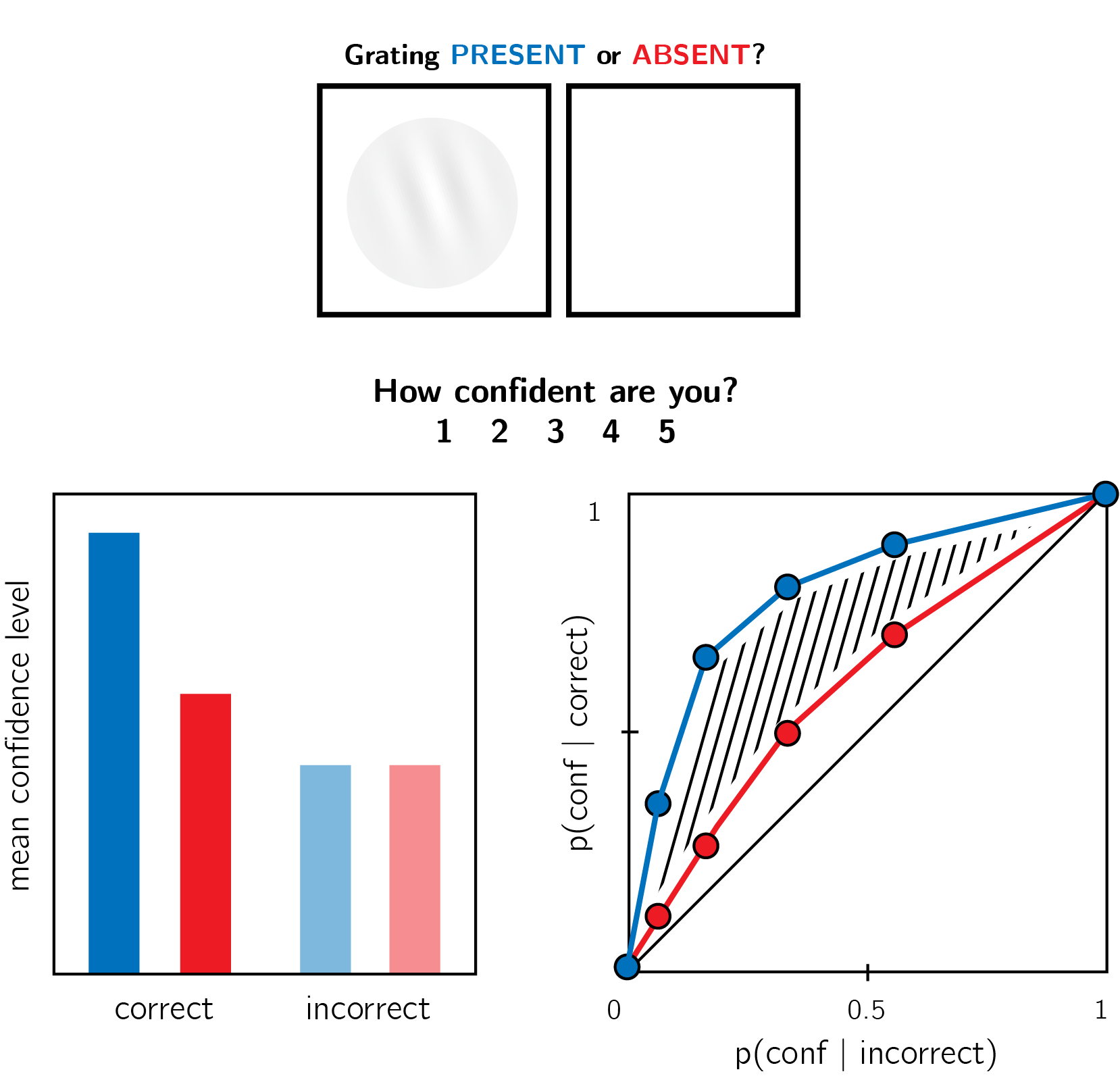

An overarching difficulty in representing absence may reflect the metacognitive nature of absence representations; to represent something as absent, one must assume that they would have detected it had it been present. In philosophical writings, this form of higher-order, metacognitive inference-about-absence is known as argument from epistemic closure, or argument from self-knowledge (If it was true, I would have known it; Walton 1992; De Cornulier 1988). Strikingly, quantitative measures of metacognitive insight are consistently found to be lower for decisions about absence than for decisions about presence. When asked to rate their subjective confidence following near-threshold detection decisions, subjective confidence ratings following ‘target absent’ judgments are commonly lower, and less aligned with objective accuracy, than following ‘target present’ judgments (Fig. 1.1; Kanai, Walsh, and Tseng 2010; Meuwese et al. 2014; Kellij et al. 2018; Mazor, Friston, and Fleming 2020).

Metacognitive asymmetries have not only been observed for judgments about the presence or absence of whole physical objects and stimuli, but also for the presence or absence of cognitive variables such as memory traces. For instance, in recognition memory, subjects typically show poor metacognitive sensitivity for judgments about the absence of memories (such as when judging that they haven’t seen a study item before; Higham, Perfect, and Bruno 2009). Unlike the absence of a visual stimulus, the absence of a memory is not localized in space and does not correspond with a specific representation of ‘nothing’.

One way of conceptualizing these findings is that absence asymmetries emerge as a function of default reasoning - absences are considered the ‘default’, and information about perceptual or mnemonic presence is accumulated and tested against this default. For instance, an asymmetry may emerge in recognition memory because the presence of memories is actively represented, and the absence of memories is assumed as the default unless evidence is available for the contrary. In the same way, other visual features that are not typically treated as presences or absences may still be coded relative to a default, assuming one state unless evidence is available for the contrary (e.g., assuming that a cookie is sweet rather than salty). However, whether a metacognitive asymmetry in processing presence and absence generalizes to these more abstract violations of default expectations remains unknown. Here we set out to map out the structure of absence representations by testing for metacognitive asymmetries in the presence and absence of attributes at different levels of representation - from concrete objects, to visual features, to violations of default expectations.

Our choice of stimuli draws inspiration from visual search - a field where asymmetries are observed for a variety of stimulus types and features. In visual search, participants typically take longer to search for a target that is marked by the absence of a distinguishing feature, as compared to searching for a target that is marked by the presence of a feature relative to distractors (Treisman and Souther 1985; Treisman and Gormican 1988). Interestingly, search asymmetries have been demonstrated not only for the absence or presence of concrete physical features, but also for the presence or absence of deviations from a more abstract default state, which can be based on experience, culture, and contextual expectations (see methods; Von Grünau and Dubé 1994; Frith 1974; Wang, Cavanagh, and Green 1994; Gandolfo and Downing 2020). Of special interest for our study are these latter symmetries due to expectation violations, and their relation with asymmetries induced by the presence or absence of local and global features. Observing a metacognitive asymmetry for expectation violations as well as for the presence and absence of objects features would support a strong link between the representation of absence and default reasoning, where differences in metacognitive sensitivity reflect differences in the processing of information that agrees or contrasts with the expected default state.

Figure 1.1: In visual detection, subjective confidence ratings following judgments about target absence are typically lower, and less correlated with objective accuracy than following judgments about target presence. Top panel: a typical detection experiment. The participant reports whether a visual grating was present or absent, and then rates their subjective decision confidence. Bottom left: typically, mean confidence in ‘yes’ responses (blue) is higher than in ‘no’ responses (red). This effect is much more pronounced in correct trials. Bottom right: the interaction between accuracy and response type on confidence (metacognitive asymmetry) manifests as a lower area under the response-conditional ROC curve for ‘no’ responses compared with ‘yes’ responses. Plots do not directly correspond to a specific dataset, but portray typical results in visual detection.

While traditional accounts interpreted visual search asymmetries as reflecting a qualitative advantage for the cognitive representation of presence (affording a parallel search in the case of feature-present search only; Treisman and Gormican 1988), other models attribute the asymmetry to differences in the distributions of perceptual signals already at the sensory level (Vincent 2011; Dosher, Han, and Lu 2004). Similarly, in the case of metacognitive asymmetries, the idea that decisions about absence are qualitatively different from decisions about presence has been challenged by an excellent fit of simple models that assume unequal variance for the signal-present and signal-absent sensory distributions, a model that does not assume any qualitative difference between the two decisions (Kellij et al. 2018). Deciding between these model families is beyond the scope of this project. However, identifying metacognitive asymmetries for abstract cognitive variables such as familiarity could help refine these models, for instance by revealing that representing deviations from a default state is an overarching principle of cognitive organization, one that goes beyond specific features of visual perception.